Disk Galaxies

Contents

9. Disk Galaxies¶

9.1. Disk Properties¶

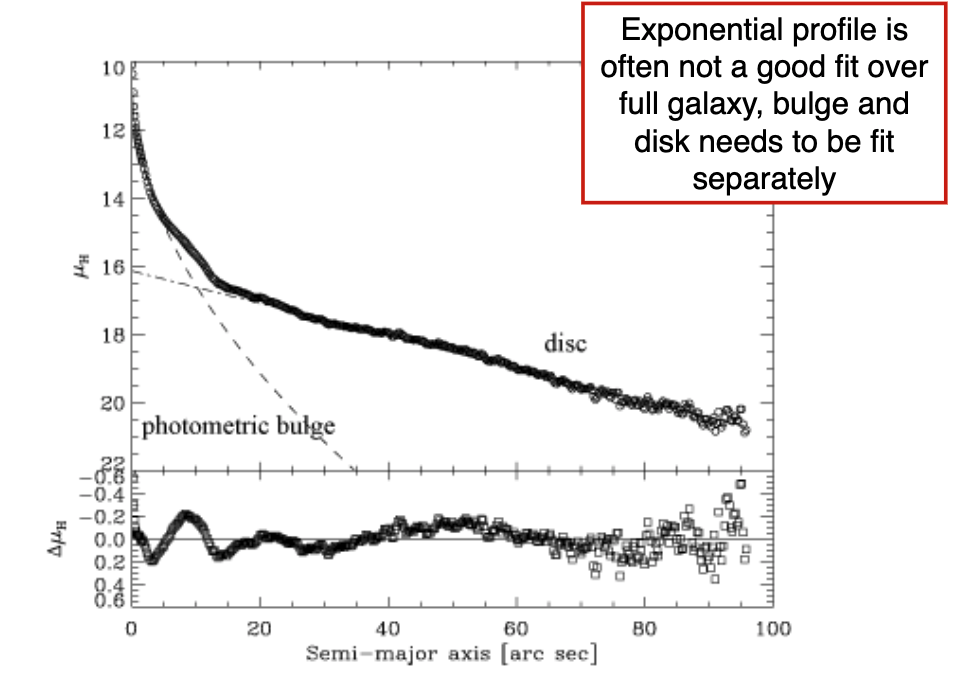

Often, the surface brightness profiles are not well fit by single componenets – there’s typically a central bulge and an outer disk which need to be fit separately.

It’s approximately exponential beyond the bulge, though.

Random Facts:

There’s a mass-size relation More massive disk galaxies are larger

Older disks are more massive and brighter

Older, more massive disks rotate faster \((\sim 150\) km/s)

Brighter, more massive galaxies are more metal rich (approximately solar)

More metal rich disks also rotate faster

Color Gradients:

Colors become bluer with increase radius/decreasing surface brightness

Later type galaxies are bluer overall

9.2. Bulge Properties¶

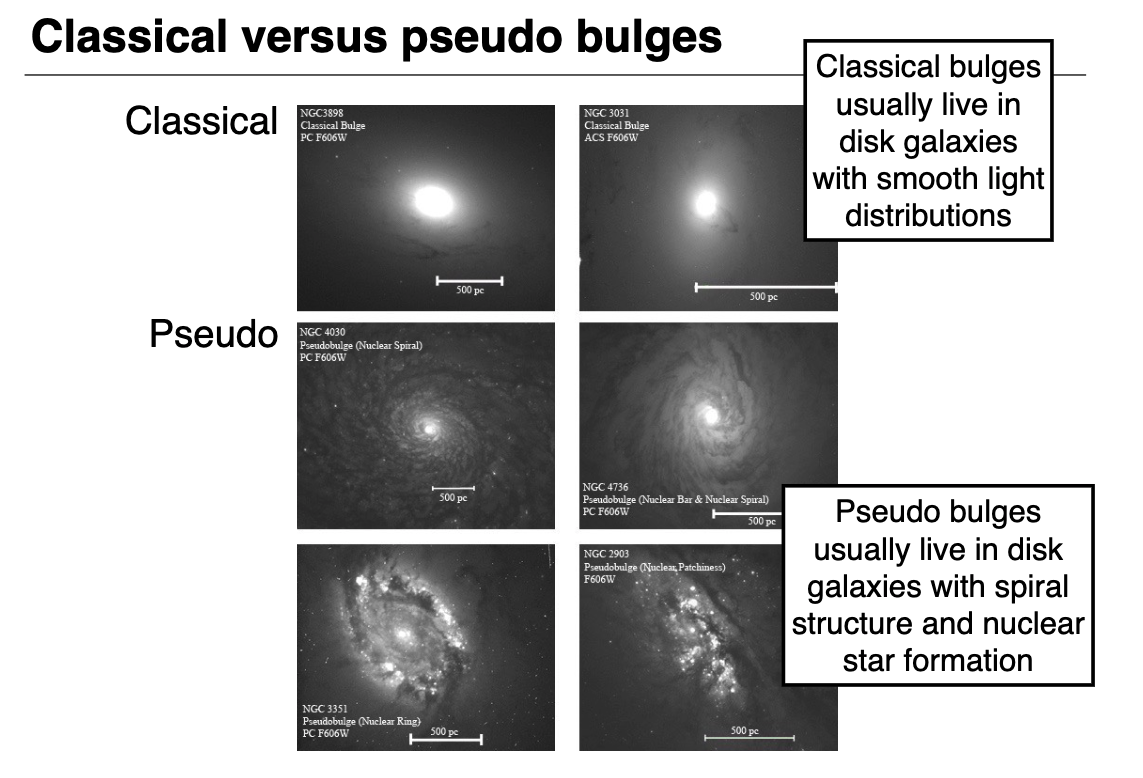

There are two types of bulges: classical and pseudo-bulges:

Classical bulges typically live in disk galaxies with smooth light distributions

They are somehwat similar to elliptical galaxies

Often do not rotate

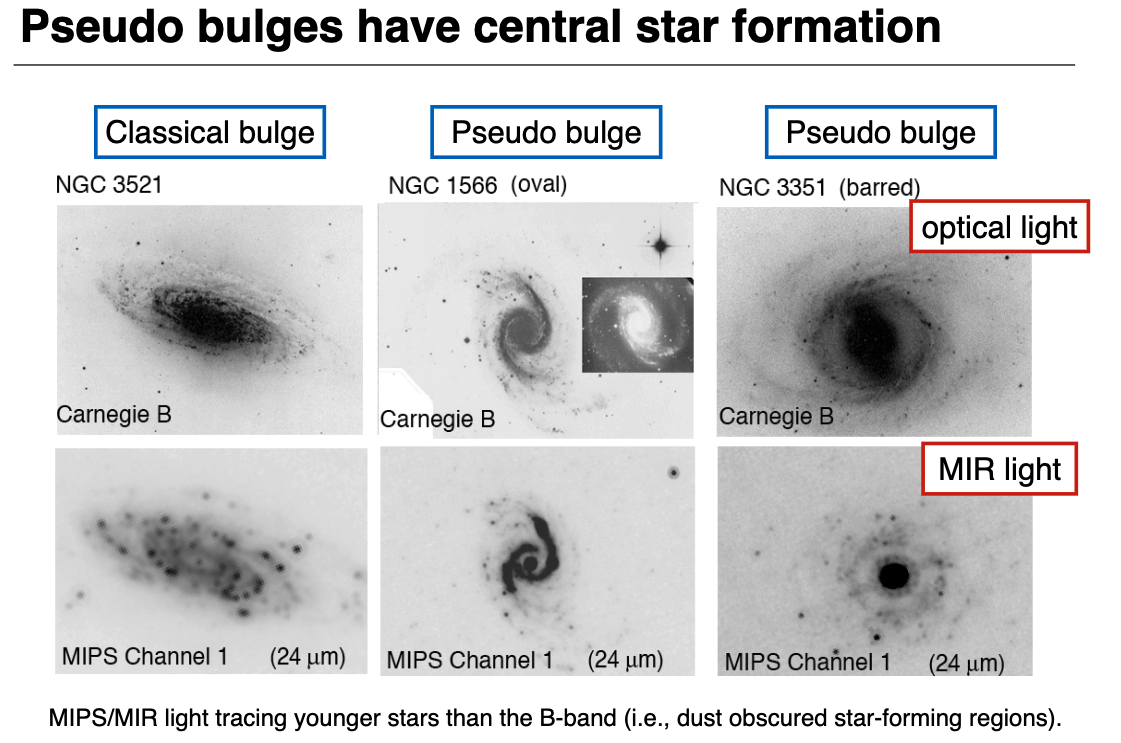

Pseudo-bulges typically live in disk galaxies with spiral structure and nuclear star formation

Light is typically dominated by young stars

Pseudo-bulges

Typically have lower Sersic \(n\) , magnitude, and surface brightness

Are rapidly rotating

Have central star formation (see image below)

9.3. Extent of Stellar and Gas Disk, Rotation Curves¶

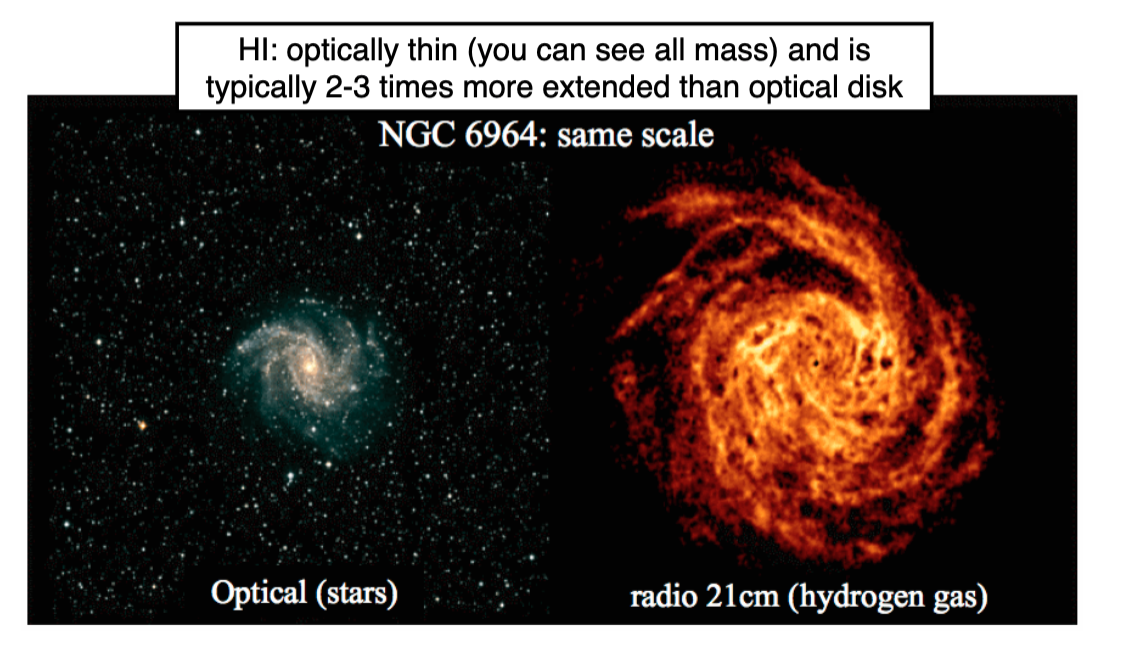

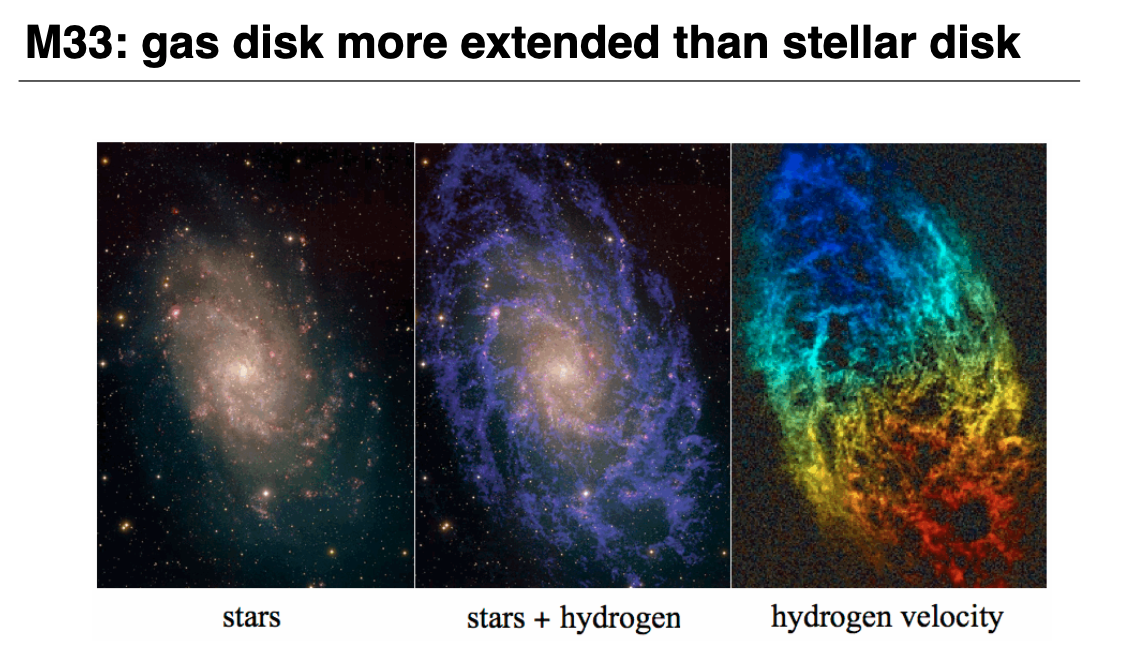

HI is optically thin (you can see all the mass) and is typically 2-3 times more extended than the disk itself

This makes HI a great way to probe the dark matter halo, and allows us to measure rotating curves to very large radii

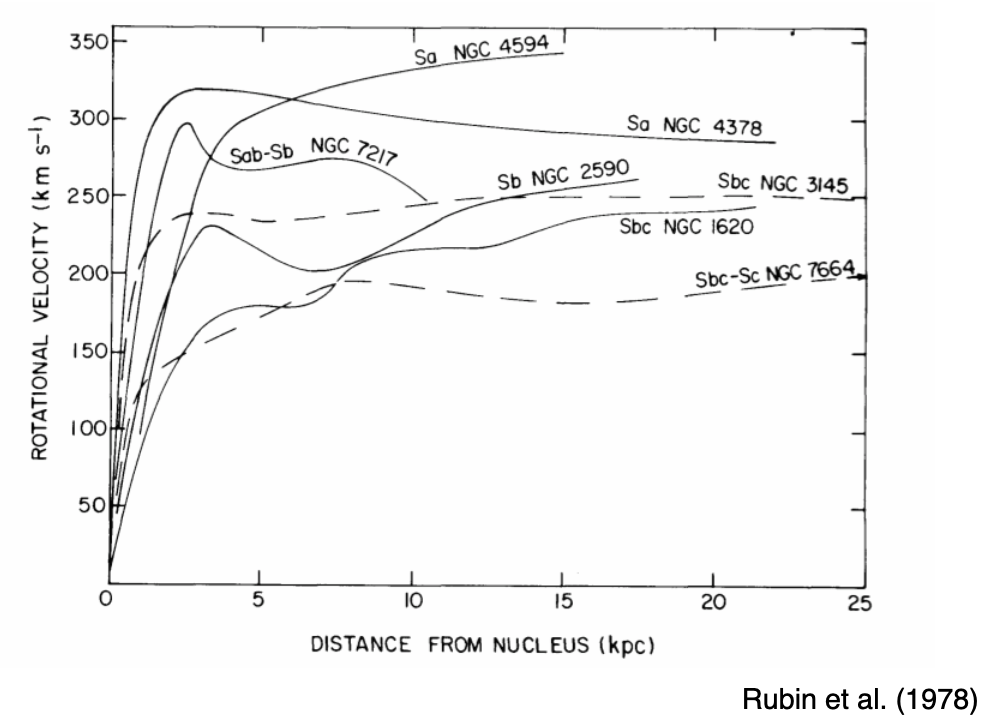

And here are Rubin’s rotation curves from H\(\alpha\):

9.4. The Tully-Fisher Relation¶

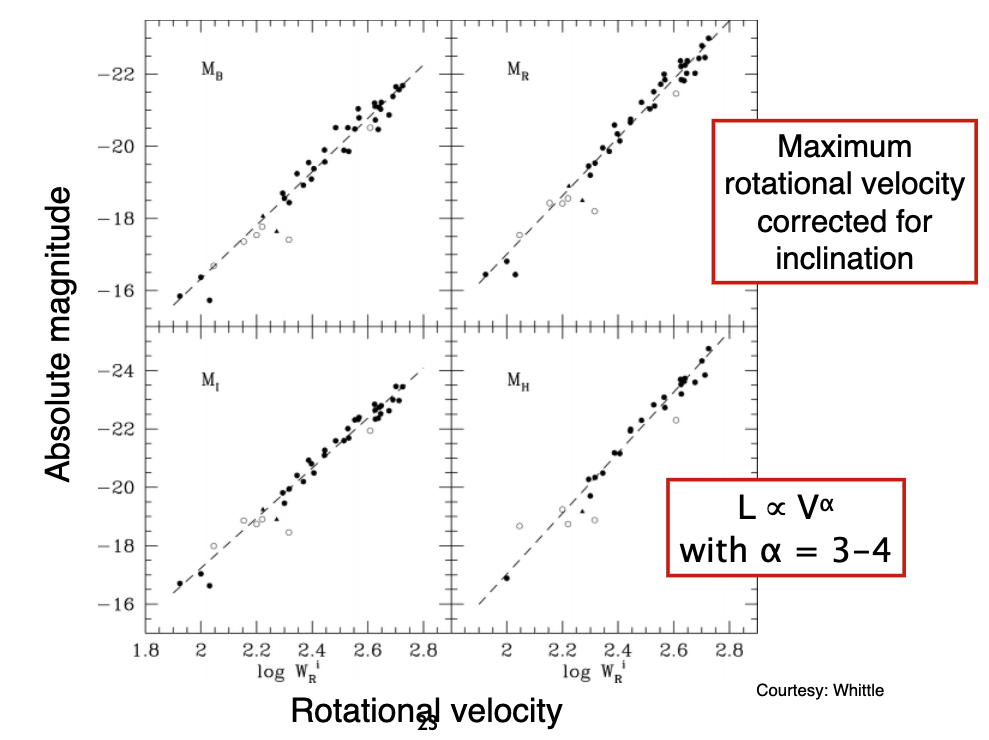

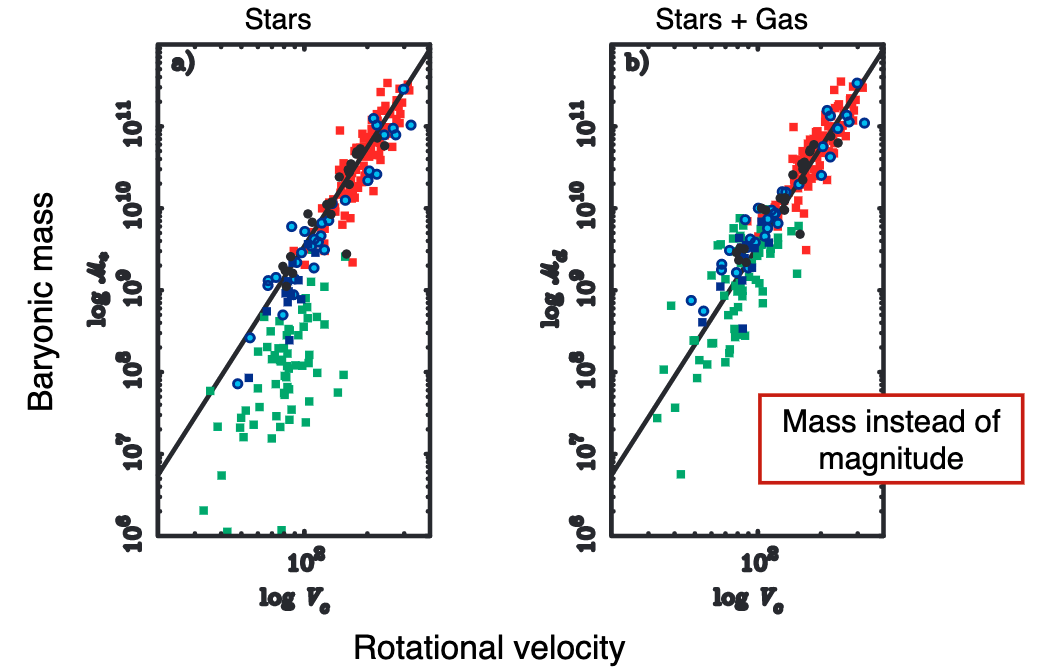

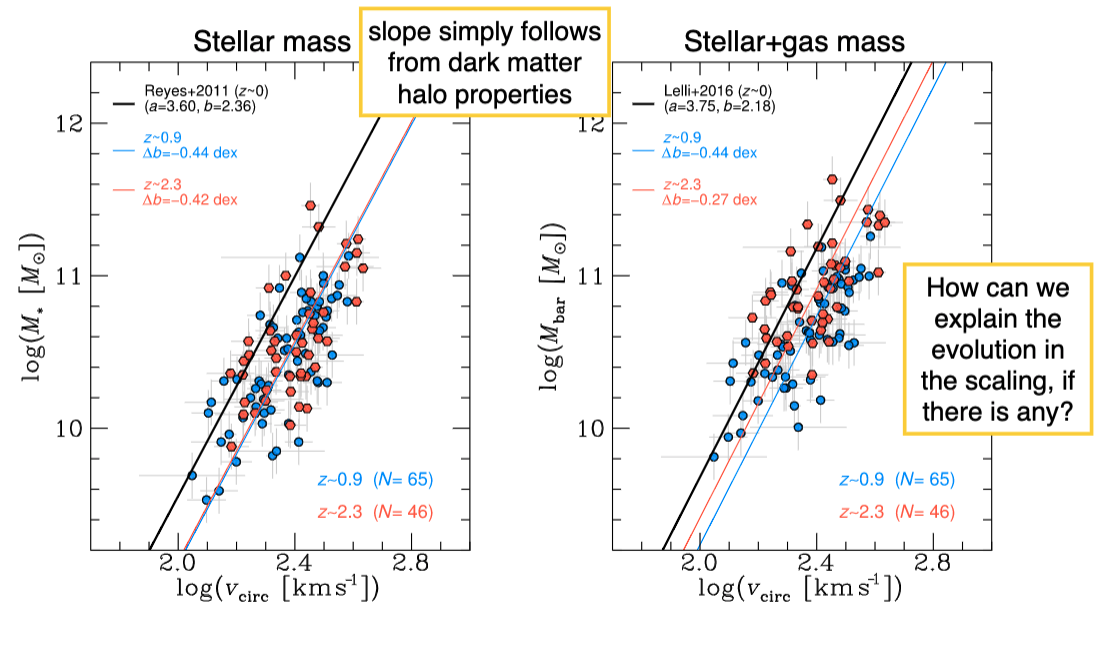

Measuring maximum rotational velocities (aka measuring the dark matter mass), corrected for inclination effects, gives a scaling relation between rotational velocity and luminosity: The Tully Fisher Relation!

In practice, you typically measure the velocities from HI, get cepheids for distances.

Another scaling relation was found between mass (instead of luminosity), and this is called the Baryonic Tully-Fisher relation.

9.4.1. Derivation¶

In much the same way we could get close to the Fundamnetal Plane from the virial theorem, we can get close to the Tully-Fisher relation.

The empirical version is \(L \propto v_{max}^{3.4}\). Let’s start with the virial theorem:

Following last time:

We now have:

Do the same algebraic trick as last time, multiply by the mass-to-light ratio:

We now assert a constant mass-to-light ratio:

We make another assertion (though it’s egregious). Let’s say we have an exponential surface brightness profile:

where \(r_0 \propto r_e\). Taking this SBP, we find:

It turns out there is a thing called Freeman’s Law, which says there is an approximate constant surface brightness for disk galaxies. Using this as an assertion:

Thus,

Returning to before:

The Tully-Fisher is powerful for the same reasons as the Fundametnal plane.

9.5. Spiral Structure¶

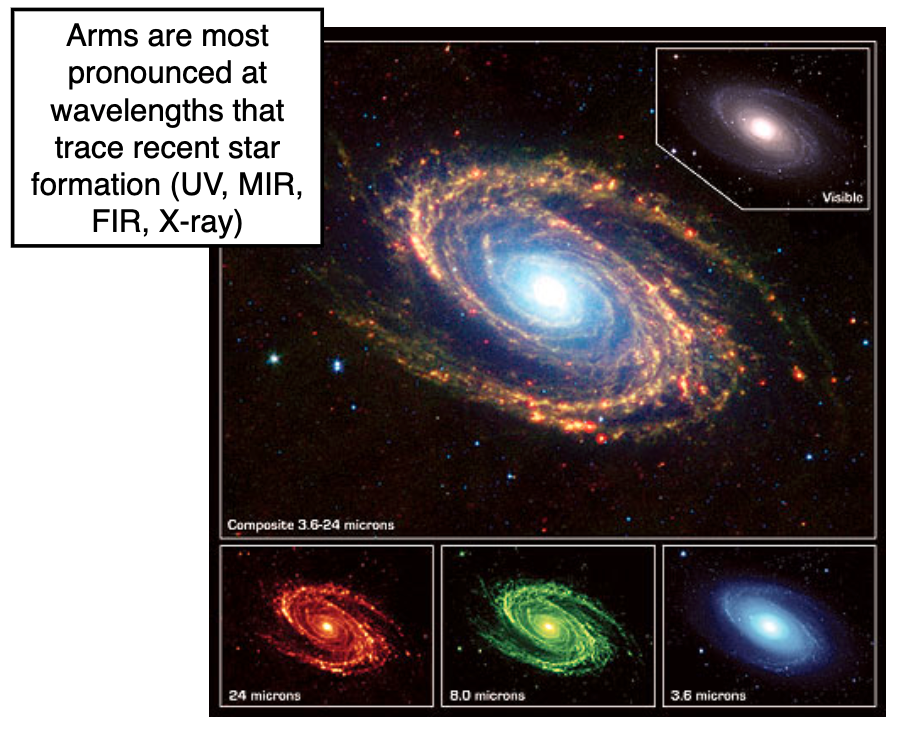

Spiral arms are most prominent at wavelengths which probe recent star formation.

Distribution of material

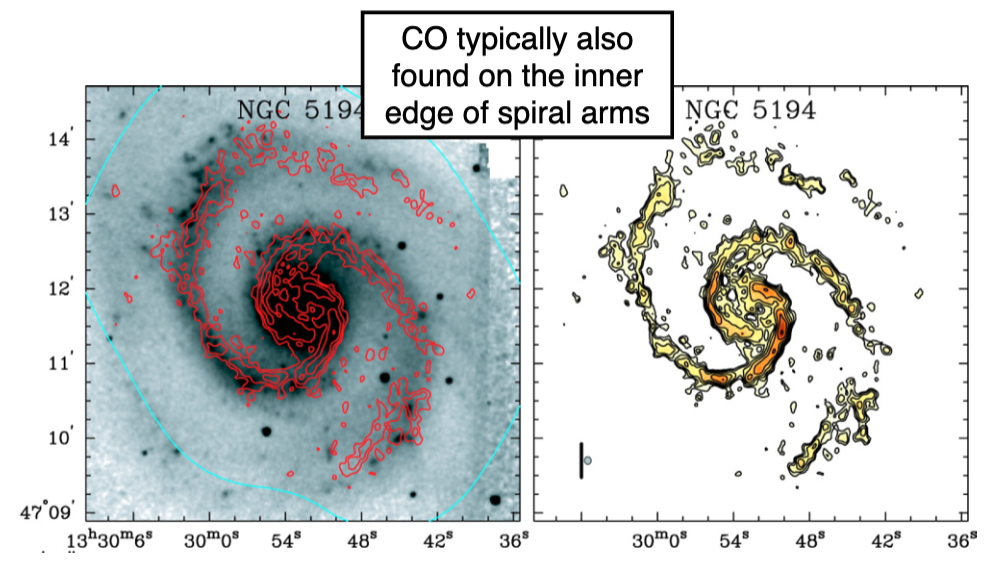

Dust lanes, CO are typically found on the inner edge of spiral arms – the sights of ongoing star formation! Stars will be formed on the inner edge and then drift behind, making up the actual arms themselves

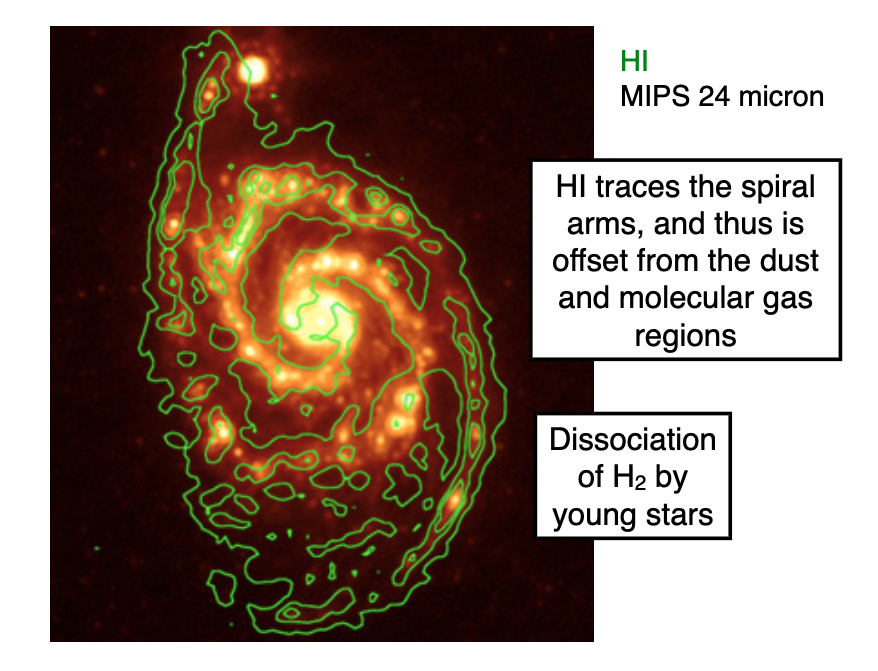

* HI traces the spirals themselves and are the reservoirs for future star formation

9.5.1. Types of Spirals¶

Grand design with two strong spiral arms (20%) vs. multiple arm spirals vs. flocculent spirals (with lots of chaos, no clear spiral arms but spiral structure)

Flocculent arms/spirals are associated with ongoing star formation

Depends on wavelength!

9.5.2. Trailing and Leading Arms¶

Projection effects make it hard to know the rotation direction – need to measure distance to front and back of spiral, or use dust obscuartion to infer the rotation direction and thus the leading or trailing arms

9.5.3. Origin of Spiral Arms¶

Flocculent structure could be the result of differential rotation, but stable spiral arms seen in grand design spirals cannot be due to differential rotation alone. The arms would fragment and dissolve much faster than we see.

Instead, we think of spiral density waves just like in a traffic jam

Maybe these originate in asymmetries in the potential which has been seen in simulation

Maybe it’s induced in galaxy encounters

Density Wave Theory

Stars form on inner arms (so more dust and molecular gas). While the new stars travel through the arms, the molecular gas gets dissociated (into HI). The most massive (OB) stars die out fast, before the stars move out of the arms. Thus you see star formation primarily in the arms.

The gas is more collisional than the stars, and thus the gas is swept up into regions more easily than stars. Stars form on inner arms (so more dust and molecular gas). While the new stars travel through the arms, the molecular gas gets dissociated (into HI). The most massive (OB) stars die out fast, before the stars move out of the arms. Thus you see star formation primarily in the arms.

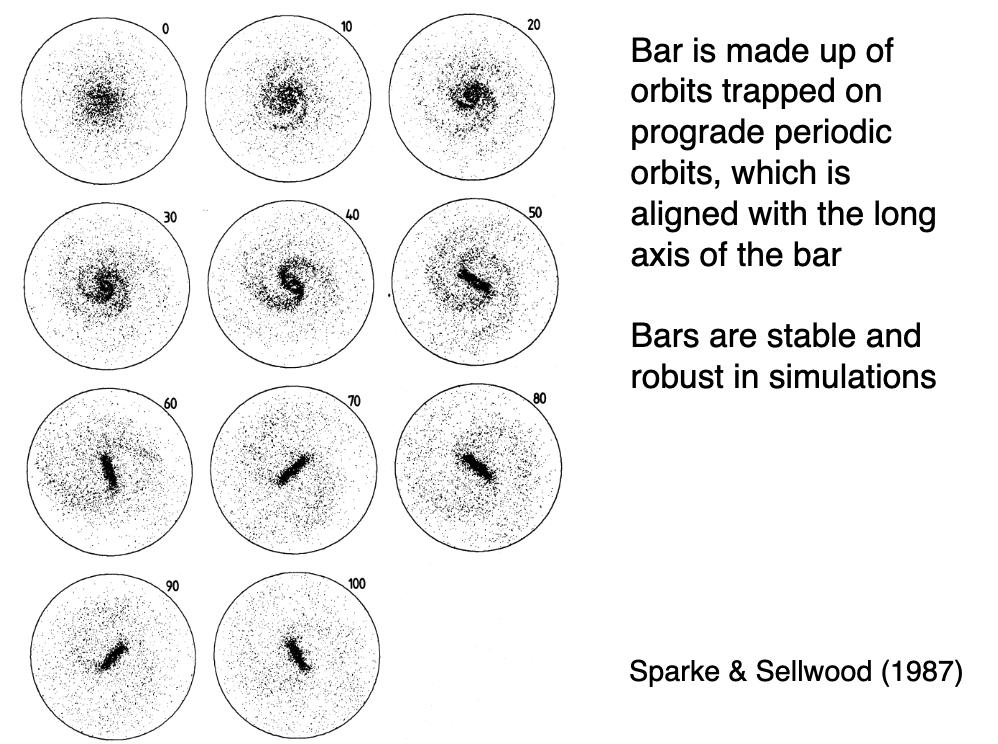

9.6. Barred Spirals¶

General facts

Common in ⅓ to ⅔ of spirals

Isophotes not fit by ellipses, more retangular

Probably flat in the disk plane

Bars are straight and stars stay in the bar

Bars rotate along with the pattern speed

Bars are not density waves but density waves likely shaped orbits of the inner stars

Bars can help drive density waves in the disk and maintain spiral structure

Bars are long-lived, easy to form in simulations

9.7. Disks at High Redshift¶

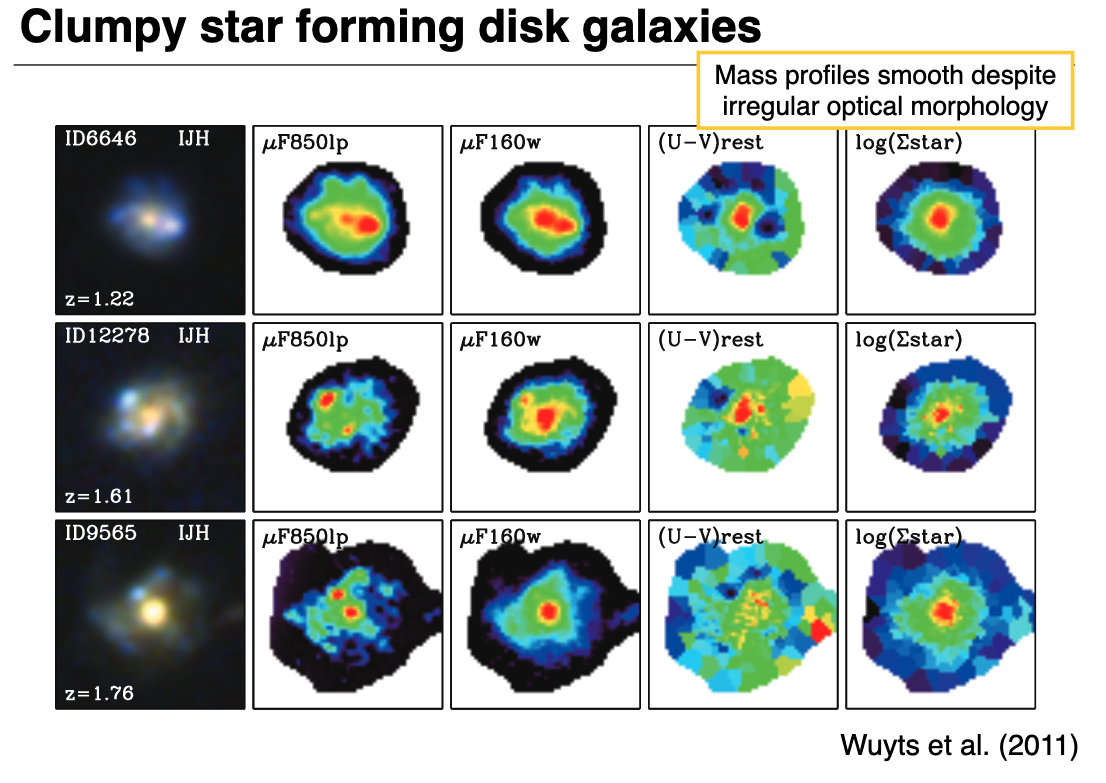

At higher \(z\), star forming disks are much more irregular and clumpy

Despite the optical morphology being lumpy, the actual underlying mass is quite smooth

The Tully Fisher relationship seems to hold at higher redshifts – the slope simply follows from dark matter halo properties.

9.8. Summary of Disk Galaxies¶

The surface brightness profiles are approximately exponential

More massive disks are on average more metal-rich, older, rotate faster, redder, and larger

The outer parts of disks are generally bluer and of lower metallicity than the inner part

Disk galaxies have flat rotation curves

Disk galaxies fall on the Tully-Fisher relation, a tight correlation between luminosity/mass and rotational velocity.